Digging Deeper: How the Ban on Engineered Stone positively impacts all workers exposed to Silica Dust

This week marked a critical moment in occupational health and safety, as Ministers determined the fate of engineered stone in this country. Introduced to Australia around two decades ago, the use of engineered stone has resulted in more than 700 accepted workers compensation claims and a prevalence rate as high as 1 in every 4 workers with a silica-related disease.

The decision to ban engineered stone has been celebrated by numerous stakeholders as a decisive victory for workplace and public health. Nevertheless, it has drawn criticism, primarily fuelled by a misconception that the ban doesn’t help workers in other at-risk sectors. However, nothing could be farther from the truth.

Contained within the Communique from that meeting, was a decision to amend the existing Work Health and Safety Regulations. The amendment will apply to all crystalline silica processes in all industries bound by those Regulations. The amendments include:

1. Additional training requirements;

2. A requirement to conduct air monitoring; and

3. The need to report exceedances of the workplace exposure standard to the health and safety regulator.

Many workers will comment that they just did not know that the products that they were using could cause incurable diseases. Sharing information on the toxic nature of crystalline silica, the health effects and diseases it causes, and the safety precautions needed to keep workers safe is an essential part of working with any silica-containing material. A specific call-out in the Regulations for training requirements is very much welcomed.

Air monitoring is the leading indicator for disease prevention. It tells us how much silica dust workers are exposed to in the workplace, providing a measurable standard for workplace exposure. It provides a comparative benchmark against the legislative workplace exposure standard.

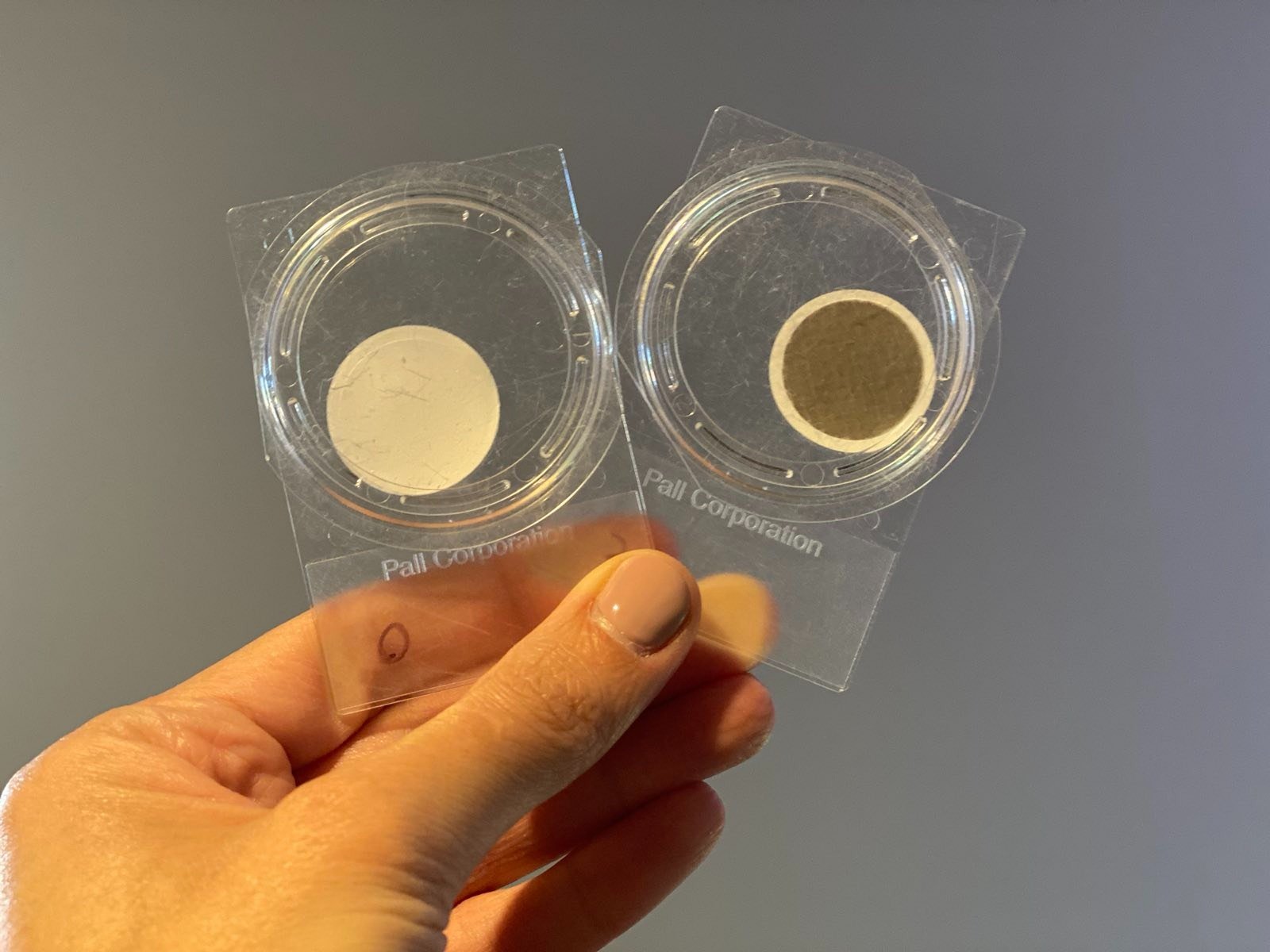

Filters used to collect respirable dust and respirable crystalline silica (silica dust) as part of air monitoring. On the left is an un-used filter and on the right is what the filter looks like after one-day of air monitoring in an at-risk workplace.

Unfortunately, many businesses have not been conducting the required air monitoring. In a 2019 review of the dust diseases scheme, the CFMMEU expressed their concerns about the lack of clarity surrounding existing air monitoring regulations. They called for clearer guidelines on air monitoring procedures. The Committee agreed; however no action was taken.

Inspections conducted by SafeWork NSW during 2020-2021 revealed a concerning lack of compliance, with only 15% of engineered stone businesses having any form of personal air monitoring report on record. Moreover, a separate study published in 2021 reported that air monitoring was not always conducted. Where it was performed, some levels exceeded the workplace exposure standard, which was concerning regarding the potential for even higher exposures.

Not doing air monitoring is one danger, but disregarding the results is even more concerning. Right now there is no requirement to report air monitoring results for silica dust to health and safety authorities, and in some instances, the results are outright ignored.

Based on my professional experience, exceedances of the workplace exposure standard are unfortunately common within at-risk sectors, including demolition, construction, and tunnelling. While proactive employers have instituted air monitoring plans, and act on the results, this approach is not universal.

This proposed legislative reform is a considerable step forward in protecting workers in many industries from preventable silica related diseases such as silicosis and lung cancer. This week’s decision by Ministers to ban engineered stone is significant, but the broader legislative reform makes that decision even more powerful in our aim to eliminate silicosis and silica related diseases across our Country.